Observations, poetry, silence. Breaking, rewiring, feeling, raging, smiling, musing, missing. Satisfaction, indignation, affirmation, consternation, web pollution. All that and just a little bit of me.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

A Super Model and the President of Bulgaria

One of the girls asked a gay chinese man to donate sperm for her baby and he volunteered to deliver a bucket. And reading the menu, someone loudly said, "There is no Sex on the Beach. We have sex on the beach all the time." And then she realized that she didn't use her inside voice and was quite embarassed. Young people, just fun and games.

I am subjecting some of them to my cooking next week. Unfortunately all I can really cook in Turkish food, a chance of never learning to cook in India and my college room mate who taught me cooking happened to be Turkish. May be, I will download some recipes off the internet and practice it on them.

Burned Turkish steak anyone?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Back in the summer of 1996 (for the mathematically challenged, that was Ten years ago), one Tuesday, my sister and I drove from Indianapolis to Saint Louis, Missouri (which, once again for the uninitiated in the ways of the Mid-West, is pronounced Missourah in local circles) to visit the University. We had not gone by ourselves on a long drive like that ever before I think. So, this was simbling bonding time. I love driving in the Mid-West, even though the scenery never changes, the roads are uncrowded and well maintained and there is a rural simplicity that is very calming. After we were done with our business, we thought we will hang around for a little while and see the famous St. Louis Arch. It is a pointless structure that looks like it is waiting for its twin so you could collectively call it McDonald's Silver arches.

To reach the top of the arch you get on a elevator-train contraption and on top of the arch (630 feet high, I just looked it up), there are windows that you can look out of and enjoy the summer day. So as I looked down, I saw a fleet of black SUVs pull up all under the arches and it looked like a major scene from CSI or Law and Order, since everyone knows FBI travels in style in black SUVs. Before we had much time to process the information, blue-jacketed men came up and told all those of us who stood in the narrow confines on top of the arch that we couldn't leave the space and no one could come up because the President of Bulgaria was coming up. And thus, my sister and I spent a few very uncomfortable moments in the close and crammed company of Zhelyu Zhelev and his myriad bodyguards, wife and FBI. He looked positively disagreeable and bored.

By the way, there is no point to this story. Just like most things in my life. And stay tuned, one day I will write about how I knocked Minnie Driver to the ground accidentally, how I bumped into Richard Gear on an elevator and sat next to the very tall Christine Baranski for six hours. You just have to get me going or ply me with alcohol.

I have plenty of pointless stories.

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

What Was I Thinking?

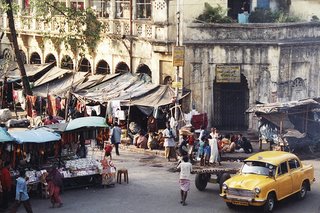

In 1989, one November evening, I was lying in bed in my room in Bombay reading Dostoyevsky's The Insulted and The Humilated. Suddenly, something stirred in me and I decided to travel to Calcutta without a specific plan. I didn't think it was prudent to tell my parents about this inspired lunacy, so I was quite resourceful in inventing a lie. The next day, I set out to Calcutta by Geetanjali Express with all the money from the National Talent Scholarship (another minor detail my parents knew nothing about).

Much of that journey I have blocked out from my memory except I remember vividly the pink cover of the Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance I was reading on the upper birth of the second class compartment. It was a miracle I was able to get an RAC birth on the same day of travel. The booking system was newly computerized and the VT booking office was granite and glass. My fellow travellers were Bengali goldsmiths who worked in Parel and going home for their annual holidays. I am sure these things are very different these days, the last time I had the pleasure of Indian train travel was in 1990 I think.

I always looked forward to the last segment of the trip from Kharagpur to Howrah when you could look out and see village fishermen fishing with wide nets in shallow mud pools. At Kharagpur, a lot of hawkers filled the compartment selling everything from glass bangles to coconut water. Bengal cam alive for me at that time.

The cab lines outside Howrah station were always long, right after geetanjali comes onto the platform. By the time, I was on the bridge, it was dark.

Does anyone remember how the leafy courtyard looked in Oberoi Grand those days? There used to be a beauty salon to the right and a coffee shop in the back. This is before the renovation. In those days, Chittaranjan Avenue was fondly called the Chittaranjan Abyss because of the protracted legal challenges to the metro extension.

There are no surprises, just bad timings.

There were tears and confessionals. There was a slow trip back to Bombay.

Why do I remember that today?

Marrakech is not Calcutta, I am told, but I just bought a ticket to go to Morocco this weekend. I am running away from all sorts of chores, such as functionally equipping my corporate apartment after I move into it day after tomorrow. But spending another weekend like last Sunday is not worth it. And all I have to finish reading is the complete history of reformation. So coming Sunday, you will see me walking the narrow streets of the Medina.

Oh, and I am told today that people of subcontinent remind others of roaches. These pesky little creatures that crawl through the more ordered parts of the world bringing disease and filth. Inside my suit, I felt like Jeff Goldblum in the fly, busting out at seams as I transform myself into a giant filthy roach. Or for the literary types, a Kafkaesque vision as in Metamorphosis.

Nice.

Earlier that evening, I had waited for a cab outside my office for 15 minutes. The shoulders and sleeves of my jacket were getting wet from my attempts to look onto the traffic. The cabbie was not too happy about the short ride. He was probably Lebanese and he played Arabic music in the cab. I couldn;t find any chewing gum in my bag. I walked down to the empty bar by myself and looked around in vein for an empty chair.

On my side, there were 3 Arabs sitting, one of them dressed in black shirt, black jachet and a gray tie and for his age, he had unusually black hair if you know what I mean. Behind me, two middle-aged British women drank their alcohol quietly. There was delicious cigarette smoke all around me. The waiter recognized me today. The Maître de circulated the room smiling and silently noticing everything. Outside, it rained incessantly. The hotel is quiet these days, most of the Arabs have gone home. The steps behind me led to a wall covered with ugly light turquoise blue wall paper. The olives had pitts in them. These details are important.

I shall never again drink a gin and tonic. I don't want to be sad. I don't want to be second best, or third act, or the fourth guy from the center in a yellowing photograph. I don't want the silence that screams inside me once the rooms and corridoors are emptied.

So, enough self-pity. Back to work. Nothing to see here. Mind your business, move on. Clear out. (Now say that with the same expression and accent of Eric Idle) And of course, don't let the door knob ... :-)

[Bad Poem deleted]

Monday, August 28, 2006

Where have they all gone?

Twenty years ago, one winter afternoon, we stood by an antique store on Park Street and laughed at a misformed and funny-looking bust of Gandhi. I think Rajeev Gandhi might have been the Prime Minister then. We thought that was tragic. In those days, Kwality was the hottest thing on Park Street but I don't remember we ever went there. We used to make fun of the socialites on Park Street. USGS has an office across from the Maidan and we went upto the second floor. The library was inaccessible and it would take a week to get a copy of the paper, the man behind the counter said. We went to the staff Geologist's office and drank tea. We had these lemon-scented wet wipes with us. In the heat, we wiped our necks with it to stay cool even though that didn't seem to have helped much.

Then it started raining heavily without warning. Real Calcutta rain. We were inside a sandwich place, I was eating something, my friend was playing with the cucumber pieces from inside the sandwich. Outside, I could see rain water making a million bubbles and channels on the footpath. There was a man who was visiting from the US sitting across from us. I think he was with a few others, admiring local friends he left behind.

We had no umbrellas, but that didn't stop us from walking. On the other side of Birla Planetarium, there were sidewalk vendors. In the rain, they covered their wares in plastic and huddled under them. We speculated about death. And laughed at how the bird poop ran down the faces of the statues in the rain. What an inglorius fate!

In the metro station, there were no traces of the rain. The stations were clean and beautiful. We were so proud of the metro. We sat waiting for the train and I sketched us sitting there. We got off at Bhabanipore even though we needed to go all the way to Tolly. We walked aimlessly until it was evening. The rain had disappeared but the buildings were still drenched and the green shutters were still bleeding raindrops. After we crossed Ashutosh college, we realized we were tired and couldn't walk anymore. The college was dark and the bus stops were full of people waiting to go home. Every few minutes, a private bus would stop and the conductor would entice the passengers to get in the bus. I never liked the buses in Calcutta. We took a cab to Southern Avenue. The night had fallen and we needed to get home by nine. All the vendors were out selling vegetables and other evening wares on the streets. We crossed the street and walked silently through the lawns around the lake. There were people there, in the dark, and we could hear them talking. We had been walking for eight or nine hours by then.

We crossed the Lake Gardens station and walked home. There was a doctor's clinic on the corner. A boy on a bicycle raced by and I was told he sang Rabeendra Sangeet very well. After you went home, I walked to Jodhpur Park alone. Outside the post office, people were still milling about in the night. I was exhausted.

I wonder if that Calcutta still exists. I wonder if you could still spend eight hours walking without breathing in a lifetime of pollution. I wonder if you still saw the bhadralok making their morning constitutional in their immaculate attire. Or has it gone the way Mumbai went? I wonder if that store still displays that misformed bust of Gandhi!

Today, as I look out of the window, I see the morning sky opening up in so many colors, just like the sky in Calcutta. I wish I could be there today, taking a walk along an ordinary road, like Prince Anwarshah Road or something. Nothing spectacular, just walking along observing the night life.

I was missing that sort of nightlife so much that last night I was looking for deals to fly to Marrakech one weekend this month. Take the evening flight on a Friday and come back on Sunday. Morocco, I imagine, has similar street life to India. Who knows, may be there is an antique shop which displays deformed statues there as well.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Truth Or Dare

you tell and i tell

and we tell the world

and the world tells us in return

hell with the wars

that we fight and want to fight

and gonna fight

in my name and yours

hell with

this moment

i die in a panic attack

waiting for a drip of truth

though i know there

ain’t no such thing as truth

so i can’t run from this panic

you block me and i block you

you cant see me and i wont see you

you board up your windows

and i get a trumpet

i go to the basement

and you pretend to be the oil truck

you run away from the din

and i become a mariachi band

because babe

hell with all lies

you tell and i tell

there ain’t no place safe enough

to sleep in peace

when we are just pretending to sleep

hell with the bombs, cursed cries for help

hell with shoe shopping when cities are flooding

hell with wine and cheese

and google clips of john cleese

what do i care about all this

when i can’t run from this panic

‘cuz i die in a panic attack

waiting for a drip

of truth

even though

i know

there

ain’t

no

such

thing

as

truth

Opera Prohibida

Same routine. Same phone call to the housekeeping for an iron. Same balding man with the iron. Things are quiet in the room and the curtains are drawn.

I was reading about Spike Lee's new documentary on New Orleans. I am quite thrilled he tackled the topic that the mainstream "media" (I use the quotation marks deliberately. The abdication of reponsibility by the so-called media in the aftermath was nothing short of criminal) avoided all this while.

I will end with this really evocative poem I read in the plane by Nikki Giovanni that is so simple yet so wonderful.

"I am old and need

to remember

you are young and need

to learn

if I forget the words

will you remember the music

if we meet does it matter

that i took the step toward you

i am old and need to remember

you are young and want to learn

let's dance together

let's dance

together

let's

dance"

Time to rest.

together"

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Insanity Delivered

He has leukemia-terror strikes through heart-he is my age-how does one collapse while lecturing-and the carefully planned life unravels

outside-rain chilled air-no smoke-no one will give me one-dregs of an afternoon's drinks-a glimmer on a tree-fades-I am left

Three in the morning-key turns-more dreams-on a beach somewhere bodies bake-on a boat-sun's menstrual blood falls all over it

At the marina-sunset has been cancelled-on account of rain-rain fucked it all up-so indoor drinks and inane conversations

His father is sick too-mine dead-it is the season for fathers to die-after a lifetime of pain or support-no closure, the bastards keep it all in

Drive fast-Mercedes going wobble-wobble on narrow roads

May be the world is scared- all this bravado will last

Until police shows up-you see-you cant talk out

Of a speeding ticket-with poetry

I say-you are so fucking right-can't talk out of a speeding ticket with poetry

Can't talk out of a small sad moment with poetry

Can't talk out of pain with poetry

Can't talk out of life with poetry

So what is this poetry good for?

If I said you will make decisions-you will think I am manipulating

I can't dance too long with a crippled leg-so I let go and fall

And wait for you to come by- when you are free to lift me up

Today-a hike on blue hills-to the top-at the Harvard observatory-I will let go

Crippled leg or not-No fucking poetry-that is for sure

And then drag half packed suitcase-into the plane

And kiss all this good-for-nothing poems good bye

Friday, August 25, 2006

A Brief History of Time

Guileless openness in your words

Strikes me as reflective.

I watch and wait amid consternation

That you will stop and the silence will crush me

The weight of your breath is upon me,

As the fading light finally melts away

Distressed about meaningless chores

We waste away the time we loaned us

Some tears of apprehension.

A Coolaid and a few mangoes later

You whisper to me, voice chokes in your throat,

My vision is a desert and you a watering hole.

Brunt of their anger and hypocritical scorn

Waits outside impatiently like guard dogs.

Their timid broadsides and their tepid fears await,

But right now we have each other’s silence.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I wrote this poem a little while ago. But today when I re-read it, I thought it needed a footnote. And the footnote to this poem is a few lines from another poem, "My House." by Nikki Giovanni.

"english isn't a good language

to express emotion through

mostly i imagine because people

try to speak english instead

of trying to speak through it

i don't know may be it is

a silly poem"

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Hard Rain Cafe

- Post Script:

It rained incessantly in the forest. Each drop larger than the previous, yet soft enough to fall on the ancient undisturbed ground without noise; when rain stopped to take a break, dew fell from the trees to fill the void that the respite from rain created. She loved to sleep at night with her windows open, with rain falling outside, and desire springing inside. That is how all her four children were conceived, on a mattress right beside the open window, with the sound of rain falling outside, with reflected rain drops mixing with Jim’s sweat on his back. With hands sliding on his back in the dark; love, rain, love, rain; until all of it became just a moan punctuated only by happiness and the full knowledge that another life was growing in her. She always knew it too, right after the moment, every time. That is how country girls were, attuned to the rhythms of nature.

Carbon colored acrylic paint covered the little blemishes on the back of the old country store. Between the mountains and the country store stood her homestead, and somewhere in between, hidden from public view with a military gray screen were portable potties, five in all, for the use of the needy passerby. Her benevolence shone through them, what a way to show kindness to strangers, driving feverishly into the forest for hiking or gawking, filled with Gatorade or Pepsi loaded from the town miles away, rushing into the store in hope of a bathroom. She pointed them to the back of the store quietly, with those thin pale fingers, smiling but without many words, until after they find themselves empty of fluids and happy to return to the store with good cheer enough to buy the knick-knacks or an odd tee-shirt emblazoned with the name of the forest.

At other times, often in evenings or early mornings in winter, when business was slow and the only patrons were the rangers and their families, she sat inside and watched over her domain with resignation and loneliness. She knew where the shotgun was kept, left exactly where Jim dropped it last after he returned from hunting for Elk for the last time, deep inside the forest, beyond where she herself had ever dared to go. It was her land, and all this rain and these mossy dreams were hers; he was but a boy from the desert downwind, without trees or rain and yet it was he who made this home, hunted and fished and made distinct prints on the mud with his rubber boots and taught his kids how to read bird calls. She stayed back in the background, cutting and cooking the meat he hunted, occasionally prodding him to take her to the town for a movie or the county fair. But that was a long time ago, before Jim heard the cries of dissolution in the rain and his eyes were blood shot from insomnia; before Jim grew a moustache and dyed his hair a young shade of brown and took to driving to the town for overnight trips to talk business with someone she had never heard of, only she knew deep inside that his friend was a her, another her in her place who understood his need for dry land and dry air.

The memory of Jim as a young man, with a clean smile and wide teeth, with earth-red arms of a desert man tickled her. She remembered their first encounter, behind the store, then just a little shanty four-pillar stop for buying cigarettes. He was looking at the mountains and she was running to the store from the homestead. She ran past him at great hurry almost bumping into him, not even smiling her usual smile reserved for strangers and scarcely with an apology. It was only until later that night that she actually noticed him when he showed up at the dinner table with her father. . He came from a hardworking emigrant family, he said between generous helpings of mashed potatoes and roast beef, his father and uncles were mechanics, each passing their trade to their sons and nephews just as they had learned it from their own fathers and uncles before them. He said he was proud of what he did, tinkering with cars, spreading motor grease on his finger tips and burying his head inside an open hood with seriousness and concentration. She never heard him asked why he had come to these parts and if he said it to her father, she never heard it. She was too shy to ask, or to make any conversation with the handsome stranger. .

This was before the rain forest became a great attraction and tourists started trekking in. No one ever visited these parts and her father seemed thrilled with the company of the stranger at supper, and later, to light a cigar.

He eventually showed up at the dinner table more frequently, until it was taken for granted that four places were set at the table on Sundays, for her, her father and younger brother and Jim. He never explained why he decided to stay back leaving behind the clear starry nights of his desert town and its cars that were in need of repair. It was better that way too, for she had begun to like his presence around the house, and once in a while she discovered her eyes resting comfortably on her while he conversed with her father who fixes his own gaze on the food. On one of those rainy afternoons after lunch, she came to know the scent of his aftershave and the grip of his hands. No one seemed surprised, least of them her father, when one evening she wore her best party dress and drove with Jim to the town for something or the other that she could scarcely remember now; the only memory that stayed with her was that of rain falling on the windshield, his arms around her and on her flat soft stomach and a heady feeling of exhilaration. In weeks they were married in a simple rain-drenched ceremony where the pastor tripped and hell on a puddle ruining his best suit, then conducting the wedding in his slacks. She smiled at herself. The wet hem of her dress was nothing unusual, except this time Jim lifted her up and carried her all the way to their bed in his arms.

Her father had invited Jim to move in with them. There were no houses nearby and he still needed the daughter to run the duties of a woman around the house, though he could not admit it; a stubborn man who wore the misfortune of losing his wife with silence and reticence.

Then she understood the depth of Jim’s love for her one night soon after when he turned to her in the sleep and mumbled how much he hated the rain and would have left this place if it was not for her. She felt it within her and her insides became moist to know the stranger from the desert had stayed back with his new gear of raincoat and rubber boots for her, the girl who grew up with rain and felt it inside her even when it was not raining. She had reached out and hugged him tighter that night, holding on to his arms until she too had fallen asleep dreaming of floating away with Jim into a distant wonderland.

Jim asked her in all earnestness if she would relocate with him to his desert town. He had talked to his uncle about a place in the family business and they would have a nice little house with cacti lining in the front for a fence, whitewashed stucco walls and tamales and desert flowers growing in the little garden. She was so confused that she asked him for time to think it over; the nightmare of rainless nights coming to haunt her every night she thought about it. The prospect of Jim’s sweaty back without the cool raindrops on it made her feel sad and withdrawn. She did think seriously though, even though most of her thoughts were interrupted by dreams of scorpions and desert snakes. Then on an afternoon when the rain had gathered unusual strength, she tore off a page from a notebook and wrote a bold "no and left it for him over the cash register of their store. No explanation was necessary and none was offered.

It was a long and bittersweet affair with rain for Jim. He loved the novelty of working around the shop first, the novelty of being a homesteader, and the young wife. He was hardworking, taking care of the little things that needed to be taken care of, lending a helping hand to her father and feeling all in all a good domesticated husband. Then, when she least expected it, he got depressed about the rainbow-colored sunsets of his native town, of sitting on an automobile in the middle of nowhere, drinking beer and watching the twilight fade out to complete darkness, resplendent with a tiara of colors and accompanied by an orchestra of crickets. These were foreign images to her, so she filled in the blanks with rain and clouds and moss in the desert and consoled herself to sleep with altered psychedelic dreams of rainy, forested deserts. She encouraged him to go back and visit the desert when all he did all day was to stare at the dark, damp sight of the mountains outside the windows with not so much as a word spoken or a morsel of food eaten.

"Go," she pushed him with compassion, " and find what you are missing."

And he left. She had not really wanted him to go, she had hoped he would stop hating the rain and loving the earth soaked with moisture; how could he love me and hate the rain at the same time, she wondered, doesn’t he see I am rain? Why would anyone want to leave this place, she had wondered then, she will not trade it for the world.

But she had asked him to go out of kindness and devotion and he took her upon it. He left for months and wrote long letters in slanted handwriting written on paper with motor grease stained edges. He missed her, but the letters never mentioned the rain or the beautiful desert sunsets. Then without warning, he returned one day, smiling and with a cherubic tan as if nothing had changed. The table was set for four again and he worked extra hard to make up for the lost time in repairing and enlarging the store and tending to the pasture.

She remembered how she had felt a little distant from him that time. She still loved him no doubt, but there was something missing. His firm grip and large smile lacked moisture and she felt he brought with him the aridity of his town, harboring in his thoughts scorpions and venomous snakes. When he claimed her the first time after she returned, she yielded a little less willingly.

For days after his return, as if on cue, her father died, after losing his voice and turning in his bed all night as if contracting a sudden reaction to the rain. And Jim metamorphosed into storeowner, and readily filled his father-in-law’s shoes as the local merchant. He brought in his on touches; he decorated the store with desert paintings right across from the pictures of the local attractions. He kept a little cactus on a pot right next to the cash register that stood there silently as a protest to the rainforest. He was the one who came up with a name for the store; “Hard Rain Café” and he painted it on a blackened old door panel with white paint and hung in front of the store. She liked the name and soon, he installed portable potties in the back, added seating and cleared the brush around for a little gravel parking lot. The family grew bigger and she lost herself in the chores of domesticity.

She remembered the birth of her last child, the ever-smiling Ava. She knew it was a girl when she carried her, feeling the movements inside her and waiting impatiently for their first meeting. That was the only time she gave birth in the hospital away from the homestead, in a sterile room painted in teal and white with no windows. There was no rain and no sound except for the rustle of surgical gowns and her own screaming. She equated the unpleasantness with the dryness of the land that brings out the harshness in people, showing off all the roughness, the sanitary politeness of hospital staff and the strangeness of being naked in front of strange men. She had a big smile and big eyes just like her father. She was to grow up to be the most sensitive of all, She tried to be the replacement for all losses, felt and imagined. Another woman in the house, another keeper of the rainforest. Yet, she was daddy’s little girl, going on hunting trips with him deep into the forest and helping him cut up gory pieces of elk meat. Ava grew up with a cherubic face and muscular arms, for a girl at least anyway, tomboyish, always standing up to her bully brothers and being quite proud to be daddy’s girl. There was something strange about Ava, she thought; she didn’t like rain. The first time she learned about it, she was astonished and terrified, as if the scorpions and snakes of Jim’s far away homeland has finally come to conquer her family. Ava liked the sun, the wonderful dryness of the town where she could walk without getting her clothes wet and her hem dirty. She liked her hair open and flowing and not imprisoned by rain gear or umbrellas. But she too, like her father, braved it all to go deep into the womb of the forest; deep where the moss is thick and the ground is soft with thousands of years of unspoilt forest building. She had hoped that Ava would be her companion, the sharer of her dreams, the lover of rain, the only other female in the household, a miniature of her own image. She wanted to live vicariously though Ava, reaching out to the nature in a feminine way, as an infant all over again, trying to touch the forest softly like Jim could never do. But Ava was a warrior, she cut into the forest with her shearing knife and her shotgun, trying to conquer and collect.

Ava also was the first to leave for college. She chose a college far away, near the desert and heat and where sun shone every day. Ava wanted her mother to help her with the move to the distant campus housing, but she had refused, content to fill her moments with dreams than the reality of the world outside. She stayed back, watching Jim and the boys share the responsibility of migrating her across state lines. She drank loneliness and sought refuge in staring at watercolors of wolves and elks. Even after the men returned with safe stories and weekly phone calls became routine, she never got used to the loss, losing weight and thinning her already thin fingers to a fine line of paleness. She spoke less and less and smiled more and more in lieu of things she no longer wanted to say to make them understand.

She remembered how it didn’t worry her so much when the boys went away. Granted, they didn’t go too gar, just far enough to be out of her reach, working jobs in town, around the corner, so they could come home for dinner in their shiny pickups when they were too tired to cook. She always cooked extra with the hope that they come and they came frequently at first. Then slowly, they found other women to cook meals for them, and keep them company and on Sundays they came with their women. They had already become strangers, men who were tall and manly, with women she could not relate to. She had also learned that all was not well with her and Jim also with the same country girl instincts that had allowed her to predict her own pregnancies. Somewhere along their marriage, one night she felt Jim’s cold hands searching her in the dark and she felt trembling and guilt in his fingers. She removed his hands from her body with gentle protest, and rolled off to a restless sleep. That was the last night those hands came searching for her the way they always did for over two decades without fail, but she never forgot the smell of tobacco on her shoulders and the heat of his body. She watched with detachment as Jim regressed to being the stranger, bearing the faint smell of jasmines when he returned home from the town and she knew that she had lost the battle. But she asked nothing and he offered up little. They built a nest of unspoken dreams where each checked in and checked out at their respective times and built colonies of fantasies in them. Hers were about the rain and about the bright green moss in the forest and he dreamt about jasmines and cactus flowers on the hair of another woman with younger flesh and warmer blood and their little stucco house in the desert. They smiled a lot at themselves and observed each other with curiosity. And in rainy nights they comforted themselves with warm brandy and think blankets and the house stood curious witness to this strange and calm estrangement.

She was not the least upset when he finally left. On his pick up, just the way he had come twenty seven years ago, but he was much older and his hair less shiny, his skin less even, his teeth less regular. She stood by the window and watched as he drove away, slowly away from the front of the house, past the portable potties and the store on to the road and followed the pick up until it shrunk in size and disappeared into the thick vegetation somewhere.

"I am leaving," he had said, "I hope you understand." A luminous halo of moist temperance rose from behind her and blocked his path. From here to the beginning, erase as it grows, she thought, all pain, all intemperance and mirth and gait.

She didn’t want to ask him for her name or where they were going. She knew. Desert smell rose from his mouth as ardence, and the cactus made his words home. Rain had stopped falling in his heart and the deep red of a powdery desert advanced in its place, covering her in its unpardonable harshness.

Jim came close to her, attempting to touch her one last time before he left, a consolation, an empty solace, transferring his guilt and sleeping scorpions to her memories. She moved away deftly, sitting down before he could get closer. Their shadows met half way and the darkness of insincerity wore her down. Go, she thought, before I ruin your memories with this dry parched shadow before me. He stood around for a little while unsure of what to do, uncollected and awkward pushing what had to be done to a near infinity, he had to leave, but the modalities of this transgression bothered him.

"I don’t want to hurt you.." he coughed.

She held out her hand and smiled as if to stop him and nodded.

The house felt empty and cavernous after that. Ava returned from her arid haven with a kitten. A cat as consolation for the treacheries of her father. She said that Jim was in the desert, but mumbled out the part that she had met him and his younger companion, a university worker. She called the cat Jag, her rain-loving Jaguar, like the wild cats in the forest; he will grow big and strong and go deep in the forest and hunt elks. Then Ava went back to her world; dry and red-faced, seeking her salvation from rain and her mother, leaving behind Jag and a fistful of memories in the mist that always hung around after sunset.

She felt the barrier between her and the rain outside grow thicker as if the nature had suddenly abandoned her. All these walls are suffocating me, she thought. I need to be outside, drenched, bedraggled, and kissed by rain and cold northern winds. The soft moss grew unseen first, and then with all vigor of the rain and life all around the house, growing around the walls and on the windows until all she saw of the outside from the windows was the sallow and green of life. She was happy with that, the darkness of the rainy days got deeper and darker from the darkness of the green growing all around her. I am rain, she whispered, and I give you life. She breathed the green in and gave out rain and filled the valleys and lakes with water and in her dreams she gave birth to many more children, three hundred feet trees and little birds to sing on them.

Her children wrote letters that arrived like little presents of anxiety or neurosis and remained unopened over the fireplace collecting moisture. The envelopes grew fat in the humid arrogance of the inside air and swelled from the bottled up feelings of guilt and shame. She didn’t need to open them; she knew the solitude and sadness of their words. The sky darkened like hard lichens and poured out frequently, her clothes grew shabbier from lack of care and her hair grew matted and dark. The house drooped with yet another coat of mossy green.

Finally the moment of truth arrived. The artist removed himself from the painting and let it fall as it would, to blend in with the nature that was all around it, waiting to be absorbed. Her death was gentle and unobtrusive. Rains fell hard that night and the kitten wailed gently and then ran off into the forest and disappeared.

Radio

When the rain finally went away and the golden sun descended from the heavens upon the paddy fields and blessed everyone with a good harvest, he sat down and took stock of the situation in hand. He was generally satisfied with life. His town, Valia Kunnu was a prosperous little town now; this year promises to be plentiful after a good harvest, and he had in Lalita a devoted yet opinionated wife. It was true that they don’t have children, but they were still young and if Bhagothi wills it, there was still time. He is so lucky. Whatever little they have, Lalita was happy with it and never showed her unhappiness, if she ever felt it, to anyone around her. They bore the indignities and inconveniences in life with dignity and patience.

In a town like this, the only important thing was local politics if you didn’t want to dabble in the affairs of the religion. Politics and religion, but there was little to choose from the two and come to think of it, there wasn’t much difference between them. Even though he never went past the tenth grade, his teachers had always said he had a technically inclined mind. He fancied himself as an inventor, a builder of things, a talented mechanic who was yet to be discovered. It was this preoccupation that led him to the newspaper advertisement he had glanced at the local paper about building a radio. In Valia Kunnu, Bhagothi had a great reputation of leading her devotees to their true quests in creative and unassuming ways. The advertisement promised all the knowledge necessary to build one by yourself, in ten days or less.

Radio was a luxury for the city-rich. They, like everything else in their world, depended on mechanical devices to bring them songs and news from around the world. People were going to quickly-built institutes to learn how to repair them even though there were not enough of radios yet. But it was the next wave, his friend Alex would tell him, as he finished a course in radio repairing, you just watch. Until now, he had not paid much attention to this. But now, it all started to make sense. It was not as if he didn’t know anything about building things. He had built a cowshed all by himself, and as a child he and his friends built a motor with coils and salvaged parts. Radio may be the most complicated yet, but he had Alex for support.

The temple festival was looming over the whole village. He decided that if he had to build it, he better start now. He walked all the way to the village town hall that passes for the library and asked if they had books on radios. They laughed; it is not every day that someone showed up asking for books. Then they wondered why a sane person like him would want to read a book like that; what was he going to do with a radio! Alex had many books, he said, but they were in English. Undaunted, he went about looking for it and the word reached a radio repair teacher at Kottayam and his secondhand radio book.

Essentials of Radio Repair and Maintenance, it read, by Jacobi and Lentz translated to Malayalam by P. J. M. Panikkar M. Sc.

He read it line-by-line, memorizing new words-- vacuum tube, soldering iron, circuit, diode... They sounded funny, but he was not about to give up. He was going to build a radio.

He sent for the radio kit and after what seemed like eternity, it arrived in a light blue cardboard box with a picture of radio outside and English lettering on all sides. He read all the instructions in the kit and looked at each piece with great admiration.

There was only one glitch. Some things matched the pictures, some didn’t, and some were missing altogether! This was trouble, he said. Disappointing, agreed Alex.

He persisted, and with Alex, slowly accumulated missing tubes of funny shapes, a plywood piece that would be the bottom, many other bots and pieces from here and there, and finally, went to Kottayam with Alex to look at big shops for things he couldn’t pick up from here and there.

It is not going to work, said Lalita, with great exasperation. She couldn’t understand what had suddenly gotten into her husband. It seemed like an odd thing for him to do, sitting there with electricthings trying to create fire and sparks. If it were something useful, she would support it wholeheartedly. Something useful!!

--Don’t you want to listen to music? He asked incredulously

--Why?

--It will expand your mind; entertain you. Bring a world outside Valia Kunnu closer to you.

--But I am happy here, with you, managing whatever little money we have, this simple life.

He couldn’t convince her. The more he withdrew into the books and the kit, the more Lalita feared for the gap between them. The radio began to become the other woman in their midst. Grandma was so moved by Lalitha’s mood enough to pray for better sense for him. For additional protection, she dragged Lalita to the temple to complain personally to Bhagothi, What a crazy idea, thevare (God), make the boy stop.

If it was Monday, grandma was at the temple, well, at all the local temples, in the early morning. She fasted on Mondays, and sometimes on other days too. She used all that time to ask Bhagothi and other gods to smack some sense into the boy.

But gods didn’t seem to mind.

For ten days and ten nights, he worked on the radio assembly. In reality, it took a lot longer than ten days. But the box said ten days or less and that is what he was going to believe. The soldering sometimes went as planned; but mostly not, and when not, he spent more time pulling and pushing at wires and electicthings, sometimes getting a bit of shock, sometimes cutting his finger tips. And then one day, Lalita heard a continuous noise coming from the other side of the house that sounded like a roar. Then some splutter. Then rumbling noises, and finally the radio came to life.

She had to take a peek.

It didn’t look like a radio, at least not like the one pictures on the box, what with welded wires, other electricthings and vacuum diodes fixed on a plywood piece. There were small lights and cute little green cylinders. A speaker sat separately on the table connected the plywood contraption by two long red wires.

She was annoyed.

--Take that away from this house, haven’t you had enough fun?

He pretended not to hear, he played with this and that, pulled at a wire and pushed at a knob and walked around the room with the antenna. Somewhere in between all the pulling and pushing, a song played hesitantly from the speaker.

News like this spreads very fast in Valia Kunnu. News spreads and becomes literature. Literature grows to an epic. The story becomes a memory and the hero becomes a god. This was news with epic potential and everybody came to see the marvel, to partake in the experience of being there so their grandchildren and their children could hear the story of the radioman from firsthand experience.

The crazy woman ambled in from the next house. Even Godman Mallikk Mathai came in his new incarnation as Swami Jagadanand. He brought with him Sayip John, the British Kathakali student. He hitched up his lungi quite unfashionably and looked in and smiled. In England, he said unassumingly, everyone had a radio.

Everyone!

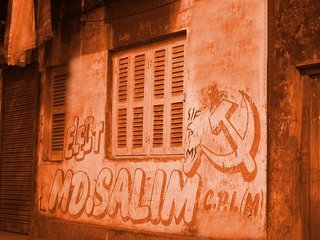

Of course nobody believed him. Definitely not Comrade Achari from the panchayat . May be in Soviet Union, but not in the capitalistic, colonial England, he said dismissively, careful to remain outside the earshot of John. He may not be a fan of the colonialists, but he wanted to remain polite. The oppressing classes will never allow the oppressed to possess such devices like the radio; he used it as an occasion to remind all and sundry in his blessed gravely voice about the evils of capitalism. This is why the Soviet Union is such a superpower. Radio for everyone and everyone for communism!

Achari was disappointed that the radio, when it produced discernable sounds at all, sang phillum songs. He was quite enraged that there was no way to listen to Russian programs, which he described as wonderful and educational, even though he had never heard Russian. But there was no one else there that had heard Russian either, and he was a graduate of the Party Leadership training session at Alwaye. That is closer to Russia than anyone else here had been to, except perhaps for the sayip John, but he was a bourgeoisie. So Achari’s assessment stood the test of logic and time.

When all he could hear was the cackling and an occasional song, he withdrew saying he had important things to attend to at the panchayat.

Everybody understood. Births have to be recorded, deaths have to be noted, licenses had to be issued for commercial activity, cronies had to be accommodated and above all, meetings had to be held, resolutions passed.

Overall opinion was positive. Everyone agreed that this accomplishment finally ushered the technology age into the village. What is next? A theatre showing moving pictures?

But Lalita refused to be swayed by public opinion. She busied herself in the kitchen, blowing into the open pit with a brass tube to fan the flames. From the kitchen, the radio sounded to her like the crackling of the wood fire.

Then, suddenly, without any reason Lalita fell ill. One day she was walking around nice and strong, the next day she was down with the worst kind of back pain. She was scared. He was scared. Grandma was most scared, because it meant that she would have to carry on with the housework all alone. Vaidya was called, medicines were prescribed, modern medicine was criticized, ayurveda was praised and as usual, the weather was blamed.

All of this had to happen just as the festival at the Bhagothi temple started. Bhagothi’s attending aediles perambulated around the preparations with great urgency and burped satisfying aromas of bygone lunches. They walked around with receipt books and black bags and knocked at every door, and where there were no doors, they dropped their heads into the mud huts and reminded the hut dwellers of their grave responsibility to keep the temple dweller happy. Valia Kunnu came on its own with red and yellow banners, with festival lightings, the loud speakers were dusted out from Narayanan’s shed to add the necessary vocal oomph to the proceedings. The loud speakers belted out songs with a lot of explosions and whistles added along the way. The mike-tester came alive and made him a standing exhibit behind the newly installed mike and interrupted the melody with his own rendition.

--Hello, hello.. miketeshting miketeshting

Children gathered under the dais and watched the self-important mike-tester and his serious business. Much of the festival depends on his ability to test the mike, the ability to carry the sounds of the festival to those far and away.

But Godless Achari, who also doubled as the President of the festival, had no time for such truculent nonsense. He ruled over the committee just he imagined the central secretariat was managed by Comrade Stalin. He was sure the great comrade would sincerely appreciate his ways of running the temple committee. Bhagothi’s opinion he was not sure, but her status oscillated between the divine and the oppressive in his mind. Once the revolution comes, it will be Bhagothi for the people, by the people, bestowing plurabilities on all people.

Everyone was busy watching silly-goings on at the temple, and listening to the elephants talking to each other while exercising their eupeptic stomachs. He took a break from the monotony of the house and joined the villagers at the temple. Elephants spoke of him sardonically in a coded language that he couldn’t understand.

Everyone had to be at the temple. Young and old. Particularly the old. And the middle aged.

Except for Lalita.

She slept in feverish solitude after he left her in the morning. Grandma finished household chores to run off to the temple. Everyone was sad to leave her along in the house, but who wanted to upset Bhagothi by not being at the temple?

So the radio took over the caretaker role for the immobile patient. Lalita complained to the radio and radio sang back at her. She was lullabied into sleep by newly favorite singers crooning right next to her.

From my eye to yours,

I will build a bridge

On the bridge I will build a castle

And imprison you in it with my love

I will be your knight in shining armor

And the dragon that watches over you

At times, the radio was like an old person, through coughing and spluttering, it spoke of old histories, the health of the market, the price of banana plantains, announced birthdays of Pinky and Sonu of Begumpet or Suseela of Cochin. Then it even played a song in their honor.

Between faint, uncomfortable sleep and the songs, Lalita fell in love with the radio. Day after day she regained her strength from the radio and got better. She got up, took a few steps, walked longer, took a bath in water boiled with tamarind leaves, oiled her hair, returned to normal life. In weeks. Slowly. Just as the festival ended and Valia Kunnu went back to its normal ways. The festival committee went down from the lofty highs of power and became ordinary citizens. Bhagothi was alone once again, sitting in the dark silently bestowing plurabilities of the multitudes even as they focused on other things.

Grandma was the most pleased at Lalitha’s recovery. He was pleased too. Swami Jagadanand attributed it to Bhagothi and the power of the festival. Comrade Achari was convinced that she recovered so quickly because she was free from the exploitative forces from the past. He secretly swore it was the radio that cured her.

Everyone agreed it was a good thing.

In the afternoon, when the village slept a languid sleep, she sat up outside in the back porch and listened to the songs. In the evenings, when the farmers brought their cattle home from a day of ploughing and little children were instructed to pray, she sat by the radio transfixed listening to the news, all the strange happenings in far away places like Trivandrum and New Delhi. There was an outside world and in its vast spaces, ministers were being sworn in or dismissed, dacoits were being killed, accidents were investigated and markets were regulated. There was a world where news and myths made love to each other in intangible ways and came alive. Grocer Narayanan was overcharging for sugar, the collector sahib was supposed to come visit every three months instead of once a year and the canal maintenance was a right and not a favor bestowed on them by the MLA.

Trickle…trickle… trickle!

Each piece of information was like overcooked rice that sticks to the palette. Each news item brought with it, undried blood or unwiped tears. There was a world out there where women worked and didn’t serve their husbands and somewhere far away there was even a leader who was a woman. She led peoples of different nations, and all of them, men and women respected her, listened to her.

And she was a woman!

Lalita changed. She became a woman. Beyond a wife, a daughter-in-law, a subject of rules and codes, she blossomed into what was Bhagothi’s destiny for her. She became a witness. The radio at times looked like Bhagothi whispering secrets to her. There wasn’t the customary bath in the evenings, the rice stayed cold, the made stayed unmade. He came home to empty rooms and empty cookware. Lalitha was out reaching out to the other women.

He didn’t understand the change. The radio was like a lover in their midst, a paramour who hid behind the drapes when he arrived.

The whole village looked at him with great sympathy.

--I told you so, they said individually when they saw him, and such things are not for small places like ours. This is not Cochin or Trivandrum!

--Once you lose control of your life, she is gone.

--Poor boy! I am sure things will be back to normal soon. After all, Lalitha just recovered from her illness only recently, they said, even though they knew this was not going to be normal.

--All of this is prophesied in the Sastras , Kali kaal brings upon us such terrible maladies, agreed Swami Jagadanand.

He nodded in silent agreement because words escaped him. There was nothing that he could really say. He was the one who built the radio. He was the one with the revolutionary idea. Lalitha had cautioned him against it.

He hated the radio. He hated this new Lalita. He wanted his old world back, he wanted Lalitha to cook and clean and wear unsmudged bindis.

The next morning Lalitha woke up late. She realized that the house was silent, no songs, no sound of news, and no discussions. For once, she could hear the water falling from the canal into the wheel once again. She got up in panic and headed straight for the table where the radio was kept. The Radio was gone. There were no clues. No one saw anything; nobody heard anything.

It just vanished! Just like that!

He blamed the thieves that were roaming the countryside, the thick mustachioed nomads from Pandinadu who were pretending to be looking for work. Have you ever seen any of them work? But look at the way they eat!

--It must be the Pandis, Swami Jagadanand agreed.

--I swear that when the revolution comes, they will be hanging from the trees, joined in Comrade Achari.

--Now why would the Pandis want this radio? Wondered Grandma. But no one really paid attention to her. If Pandis can steal brass utensils, they can also steal a radio. Besides both Swami Jagadand and Comrade Achari agreed that this was the most probable cause. After all, this was kali kaal.

Lalitha knew this was not true. But there was no proof. Her heart ached, the pain grew to longing, longing became desire. Somewhere in the midst of all that, a great weight of loss settled in her. Like the memory of a dead child.

In the months following the harvest, long after the fields had turned gold and then brown, peace remained in Valia Kunnu. Children took to playing with old cycle wheels and adults stood around discussing how to appease the Gods. He took up reading the newspaper at the far-away town library. Lalita too returned to her unsmudged sindoor and cooking.

But now there was a wider gap between husband and wife, and the bridge between them, in disrepair, remained uncrossed.

Under a newly planted coconut sapling, the radio continued to sleep its blessed silent sleep. Only Bhagothi could smile a sad smile at the radio lying in the dark moist earth under the roots.

When nobody could see, Bhagothi hummed:

From my eye to yours,

I will build a bridge

On the bridge I will build a castle

And imprison you in it with my love

I will be your knight in shining armor

And the dragon that watches over you

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

Romantic Rain

This theme is repeated in movies as well. Notwithstanding the cleavage-revealing and skin-transparency possibilities, filmmakers love to show the loving couple gyrating to the tune of some song in the rain. (My favorite, no matter how down market it might be for you, will always be Smita Patil and Amitabh Bachhan in Namak Halaal.)

And love hurts. Love is supposed to make you feel sad. The pain of love is what you pine for; you sacrifice, take on the woes of your lover and wait for a better afterlife.

On the other hand, in the West, love is always a beach. It is a sunny day. It is warm. And it is happy. And while you are at it, back that booty up.

Love is happy. If it doesn’t work out, there are other fish in the sea. Love is fulfillment. The clouds are gone and the sun is shining bright. There are no clouds in the sky.

When I think of a perfectly romantic day, what often comes to mind is warm rain. I cannot conjure up a very warm, sweaty day at the beach as the ideal for romance.

May be it has everything to do with my childhood. The monsoons were such great fun. When it rained hard, I will go up to the terrace of my apartment building and soak up all the water. My skin will turn pale under the pounding of the rain and my face would hurt. I would be in seventh heaven, just standing there getting wet and looking at the whole city getting drenched, from the fairly sterile building top.

And during vacations, when it rained, we would take large cooking pots (these were large enough to seat an adult and three or four kids) and use them as makeshift boats to paddle around newly formed ponds as rainwaters surged.

Things are different now. Now I feel like I have to run inside and get an umbrella whenever it rains. And the rains in the cities just highlight the dirt even more. I am sure if I went back to the places of my childhood, I would find the depressions that used to become ponds have been leveled and buildings built upon them.

Slowly, you have no place to call home, no place to go back to. The only home is what you have in your heart. Times of India became a rag of the worst kind, journalism was replaced by page three gossip, TV shows incessant idiotic dance numbers and romance comes ready-made with designer labels.

This morning, as I was driving to work, my iPOD was playing a series of rain songs. Randomly. Then, suddenly Asha Bhosle was singing with Kronos Quartet. I had gone to a concert recently in the US to listen to her sing with them. It was sad to hear her sing off-key and her age was taking a toll on her voice. But that is life.

Nothing remains the same. Not even the rain.

Tuesday, August 22, 2006

Valia Thampratti: The Matriarch

She must have been pushing eighty then, and her hair, silvery with that musty smell of antiquity, was finally cut short so it was easy to manage. That made her look like an old man, with even a few overgrown white whiskers under her chin. How times change a person! From all accounts, she was striking in her youth. She had to have been, for she was the stuff of legends; even then, the stories of her youth are whispered and not spoken loudly and shared by mothers and aunts to their daughters and nieces. I was just an unintended recipient of these family heirlooms, like most other things in this family, collecting them from behind closed doors and from unseen corners.

Valia Thampratti did not become a legend, a keeper of secrets overnight. There must have been many rainy evenings and dark musty nights when she listened to her shaky heart and reached out to things that she should not have, knowing well that often the consequence of these transgressions was death. May be not her own, but that of those who aided and abetted her misadventures. She was protected both by her place in the world and by the antique teak doors that firmly kept all the evil spirits out, and all stories of those deadly adventures in.

In the village of Valia Kunnu where I am from, my family ruled over the smaller denizens with contempt and condescension from this house on the hill, and the patriarchs that presided over its affairs from grand easy chairs in our front porch looked upon this as benevolence. They dispensed justice and issued orders from our front porch when they were otherwise busy entertaining each other with Sanskrit shlokas and grand stories. Their ringing laughter, accompanied by generous undulations of their bellies, traveled into the house and kept us all in check. I was a mute, weak-sighted boy, just a little insignificant part of the large cobweb that was our family. My being mute suited everyone just fine, which meant their secrets would be safe with me. In my presence and secrets came pouring from all directions; sometimes right in the middle of the day, the chaste women shared inappropriate stories of desire with each other, the stories that revealed feelings that have been long denied to them in public. Their words became serpents and hung on my neck at night, choking myself with great guilt for the pleasure I took in them. Doors that would be closed to the other children, were thus opened to me; I became the keeper of their secrets, even if they didn't intend it that way, and in my boyhood, however inadequate that might have been to the truth-knowing adult women around me, I must have stood as a surrogate pleasure check, as if being able to speak in front of me without reservations somehow freed them from the guilt of having the thoughts at all. Valia Thampratti was pointed at and mentioned, and even with my weak eyes, I could see that the name evoked strong reactions, pity and jealousy at the same time, in the speaker and the listener, as if it was she that started them on this path of vocalizing, even if they didn't dare follow her path of self-discovery.

My fellow-children in this large rambling house of co-sharers of misery and maladies grew up with other guilts. They grew up indulging in physical discoveries, climbing walls, perhaps thinking and talking about the great things that they were going to say and do when they too became adults. I didn't have to be anyone when I grew up; what could I be, mute and near blind, so I watched them through my weak eyes and grew inwards. The secrets of the house became my escape, my own pathway into the otherworld, where adults opened their mouths, disrobed their niceties, and exposed their vulnerabilities. It was in this world that I belonged and wanted to be, even after my eyesight faded away completely. I wanted to belong. And these stories were going to be my guide to the dark insides of the nalukettu when I would wander its halls alone, in perpetual darkness, long after the seeing-speaking children have gone off as adults into the adult world, seeing and speaking; doing all the great things, they were sure they were going to do.

I will stay with my stories. Like this story of Valia Thampratti.

Valia Thampratti grew up here, with many other children, all together and yet all unto themselves, noisily in the company of each other and silently in front of grown ups. With a father unusual in his interest in his daughter’s welfare, she blazed the trail for being the first girl allowed out to study from this matrilineal family, became the first to swim in the open pond with Lilly and Lotus blossoms, and the first to challenge her place, her very existence. Perhaps all these firsts got her a reputation that was to haunt her when her patriarchs went looking for a groom for her.

She was beautiful: jet black hair oiled and scented, heaving bosoms that grew and fell to the sighs of onlookers, fragrant skin uniformly the color of wheat, and a luminous smile. She sang well too, when persuaded by the womenfolk thirsting for some diversion.

She was wed when she was eighteen, late for a girl of her time. Her husband, Nilakanthan Namboori, was fourty-seven and it was his third marriage. Namboori was a phlegmatic, complaining sort of a man with yellow skin and a receding hairline, in his own world of spiritual autocracy and was not all that interested in the prospect of acquiring another young bride. The financial equation made sense, the family was renowned and what was the harm from this alliance? It was not as if he had to support her or even be a companion to her. If she was in need, she had her family to take care of her; he was a bedfellow, a visitor to the sleeping quarters of the big house after dark, with his paan box and his fan made out of palm leaves. I don’t know if Thampratti ever saw him during day light, on the wedding day she was surely too shy and uncomfortable – disgusted as well, I have heard others mumble, but I don’t know-- to look at him directly. At night, when the only light indoors being the faint glow of oil lamps, she couldn’t have seen him that well, which explained the seven children, three still-born, that were born to them. Shortly thereafter, he started visiting less and less frequently, I don’t know when, but somehow, somewhere along the way, it was taken as a matter of course that she was alone once again. Nobody really cared one way or the other, this was how things were, and anyway, it really mattered little, since he wasn’t much more than a sire for the children.

She still blackened her eyes with kohl and reddened her lips with betel leaves and laughed the same way she always did, bosoms heaving. Her sandalwood fragrance never left her and her freshly starched white clothes remained clean and well cared for.

Nobody knew why.

Nobody really cared. Well, they would have preferred if she laughed a little less. Nobody liked a married woman laughing like that. It was not proper. May be a little at night, once the lights went out, if she was with her husband, but not otherwise.

She laughed nevertheless but was careful to confine her laughter inside the house out of the earshot of the patriarchs to give them cause to worry if she was up to something unthinkable.

But in her laughter lurked a secret. A secret that made her happy in a way most other women of the house were not. Nobody, even after it was revealed, knew when it had started. Without anyone to tell their stories from their memories, the beginning got addled and atrophied under the weight of the end.

I have to guess that it might have been during the rainy season, when the weeds grew with a wild passion and the relentless beating of the water made everything slippery. Kadatha was called upon to pull out the weeds from the house grounds. No respectable home could allow wanton grass to grow anywhere in its property, not even a stubble of grass, and there was no proper way to dispose off the grass than to pull out each blade with hands. As it was the custom, the pulaya women usually did this work; the grass fed their goats and the grounds stayed clean even if the women of the house and the pulaya women stayed out of sight from each other. But this was the year when the Goddess, Bhagothi got angry and the women folk were the first to feel the worst of her wrath. One by one, they fell and succumbed, leaving a only few behind to nurse and bury the ones that departed. The women, that survived were too weak to come out and face the light, lest Bhagothi should get mad at them again. Our patriarchs, sure in the knowledge of their place in the world and therefore the importance of clean grounds in the scheme of things, resorted to ask Kadatha to come and do the work his women would otherwise have done. Kadatha came with his nephew Kannu, strong and dark as ebony, with deep blue curls like Krishna himself and with a clean strength.

The scent and memory of death was fresh in Kadatha’s mind. While he saw only the grass that needed to be picked and the sun that stared at him intently from above, Kannu was distracted by the laughter coming from inside the walls. When Kadatha busied himself on picking the grass blades, Kannu dreamt and fantasized. Dreamt and let his fingers work and wander on the grass and his mind escaped its shackles and wandered into dark corners of forbidden knowledge. He worked, listened and dreamt until, his sweat and fantasies together brought upon a fever that couldn’t be named, couldn’t be spoken of; he shivered in the silent denial of his passion and exulted in its presence.

Kadatha was scared. He thought Kannu was glanced by the angry eyes of Bhagothi too, just like the others in his family. His fever, flushed face and wandering, listless hands worried him. But Kannu knew that it was the laughter and the feeble sound of songs from inside the house that made him feverish, the sound of an invisible heart, full of passion seeking him out. Even if the voice didn’t know he was there to listen, he could feel in it a longing for him.

It was a fortnight gone before Kannu worked up the courage to find out the reason for his fever. He knew he was about to do something unthinkable, next only to insulting the Goddess, perhaps worse, but he had to do it for he was driven by nothing else. It was not a choice, but a burning compulsion that made him mark his body with small cuts from the edge of his sickle, and watch the blood drops fall. He carved his memories with those small cuts on his thigh. With each passing day, and each unconscious laugh, his thighs burned from fresh cuts. When the rest of his clan mourned loudly in rainy, moonless nights for their dead, Kannu wandered the house grounds, quiet as a mouse, lost in his cause, drenched and weary. The house walls were covered with heavy green moss, characteristic of the rainy season, and made the skin of the walls slippery but soft like a woman's skin as he imagined it. He stood near the walls caressing its textured greenness, panting, and listening for any noise from the inside, when the whole world slept. The wrath of a potential discovery did not intimidate him; he didn't think of it at all.

The rain intensified as the days went on. The ground under him had melted into clay where he stood every night listening and he felt his feet digging into the soil. He heard his breath over the noise of rain hitting against his body, crickets, frogs and all the nightnoises that came alive around him. He scaled the wall without any premeditation, slipping, falling and scaling again, each time reaching higher, with the determination of a madman and the skill of a lizard. He climbed drawing a green and brown line on the mossy wall under him slipping and scratching struggling to reach the top.

Thampratti thought she was dreaming. That night the whole sky had poured into the courtyard and she couldn't see a speck of light. She woke up with a jolt as if a feather had touched her, or a breeze had kissed her all over. Gathering her clothes about her, she walked up to the corridor and stood there holding on to a pillar, as if waiting for something to happen, someone to appear. There was a sense of anticipation, driven by instinct. She felt her feet getting wet from the raindrops and her hair feeling the leaking drops from the tiles. She chewed on a thought or two and smiled to herself, her teeth shone, even in the darkness, in their pearly whiteness.

He stood right behind her, still bleeding, wet from head to toe, eyes burning, breath muted. She had to have known, how could she not? When she turned around, she didn’t scream.

Even when the rains receded and the moon changed cycles, even as silence descended on the grounds save for the noise of crickets and frogs, they continued to meet, under the omniscient silvery moonlight, away from sleeping eyes, away from all the walls, their skin knowing each other the way they were not meant to. His skin smelt of fish and fields, hers of sandalwood paste and turmeric. For the first time, she learned of the passion men felt for women and somewhere within her a dam broke and she washed the mud and dirt on his face with her tears. They never spoke, not a word; when they communicated, it was in grunts and animal noises; they had nothing say to each other. There was an urgency in each encounter that they didn't want to waste in words. Perhaps, in the absence of language, they sought and understood all that was needed to be understood. Perhaps without speaking, without naming what was between them, the fear was kept at bay. Whatever the reason, they drank passion from each other; the more she drank from the forbidden well, the thirstier she got.

Until the Goddess lost patience and unleashed her vengeance upon Thampratti. For fourteen days and nights she lay burning, moaning, half conscious, suspended between life and death, and delirious; she slept with one name on her lips, feeble as it was, it was spoken with a firmness and resolute conviction that her caretakers understood her. She called for him unconsciously, intermittently, even as her lips were wetted with Ganga jal to prepare her for the journey that was about to come. She called for him, with a familiarity that was frightening at once for its contempt of the norms and the tenderness that only absolute deprivation brought.

In her memory, Kannu was re-reborn as a human, equal to her with a name and not just a marker, with an identity, with feelings. Unbeknownst to him, he came through the wombs of her words and startled the walls of the house, the older women of the house shuddered, cried, praying quietly for her death. They paced and wondered. They whispered in horror.

First, only to each other. The husbands heard it next. The news traveled slowly to the front porch and the patriarchs heard it, as they sat decisively in their grand easy chairs, wearing their sacred threads and gold chains, clutched their rudraksh beads. As they deconstructed the meaning of the cryptic message from inside they turned pale and ashen. They too paced and whispered. More people were consulted. Decisions had to be made, lessons had to be taught, stories had to be suppressed, examples had to be set and most importantly, the Goddess had to be appeased. They understood the wrath of Bhagothi completely and that fear grew into anger and anger was manifested as hatred. Money changed hands. Hands were washed. Then the patriarchs went back to their evening prayers and grand dinners and as night fell, they slowly sneaked into their mistresses' quarters.

The moon rose and settled. Kannu, without much warning or even the knowledge of what happened, paid the price. Nobody saw anything, but even if they had seen anything, they would have been well advised to forget anything they might have seen. Kannu perhaps went away for a long journey, perhaps slipped and fell in the river while cutting reeds, perhaps became a victim of the angry Goddess. Nobody talked, not loud enough to be heard by others anyway. It is not good to talk, to speculate about these things. These were matters of the big house.

Thampratti didn’t die. She work up from the disease weak and forlorn and after many nights of waiting, learned what she one day would have discovered. The patriarchs, in their wisdom, sent her packing, to a far away house; to rest and relax, to grow out of the weakness from the illness, far far away from home. In the nights, however, she still moaned Kannu’s name in half sleep.

When she returned, many monsoons had come and gone and many festivals were celebrated and forgotten. The house had changed; the faces sitting in the front porch were different, but just as stern. Nobody in the front porch acknowledged the memory of this tale of minor inconvenience. Except perhaps at the edge of our Valia Kunnu village, where Kadatha and Kannu had once lived. Deep inside the entrails of the house, where her nieces and cousins bored in their monotony, whispered it to each other, adding and augmenting the story, retelling the story for further effect, perhaps even after I had heard it.

The burden of being the witness.

I picture Valia Thampratti still sitting there, on her chair, chewing paan and laughing. But somewhere inside her, a cruel jester turned the wheels, laughing when she ought to have bene crying and crying when all is silent and quiet. They said she had gone mad. I know somewhere deep inside, where light and sound are frustrated by the tall, slippery green walls of her mind, she was trying to reemerge, frantically trying to communicate.

I don’t know. I am just a witness.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

1 Coll. Address for a Matriarch of Noble birth

2 Betel Leaves with paste of lime

3 Big Hill

4 Couplets

5 An architectural style for traditional homes in Kerala with the rooms facing an open courtyard inside. Rooms would normally have no windows on their external wall.

6 Brahmin

7 A Dalit (lower caste) community

8 Goddess particularly worshipped by lower castes, Coll. For Bhagawati.

9 Small pox

10 The Shepherd God

11 Water from the Ganges, often given to the dying to prepare them for death

In which he has the blues

What to do? We are like this only!

So this morning, he comes to work all ready to throw himself into meetings and forget all about yesterday. He is going to focus on real life today, even though, deep inside him he is feeling a little depressed. Confused. Sad.

The question in front of him is this: Should he let go of all this mumbo-jumbo about feelings and throw himself under the cold-cold edges of work and forget about everything else OR should he continue to allow himself to be hurt because there is some sadistic pleasure in these lacerations of the soul? He doesn't know the answer. He thinks that sometimes he allows others too much power.

He has a million phone calls to return and people are waiting for him to make decisions. The door is closed and he has such an inertia today.

So this is what he is going to do today. He is going to go eat lunch and come back with focus and happiness. May be he will arrange to have a drink with friends after work and finally catch up with others over the phone. He is going to go for a drive before the sun sets, with sun-roof open and his speakers blaring with something really peppy and silly... If all this doesn't fix his blues, he knows he is in a bad shape.

Is there a link between too much flying and depression? Does anyone know?

Monday, August 21, 2006

Ghost Stories From the Village House

These stories happened in my ancestral house in India. Like most of those houses, it is a rambling many-roomed creature with its own emotions and feelings and moods. It is surrounded by lots of land (much of which is now cut up and redeveloped but this story pre-dates that). It has a few (now non-functioning) traditional pools/stone-paved tanks in the back with wide stone steps descending into it. My grand mother, when she was alive (which she was then, otherwise, it would be a double ghost story) was very fond of taking her morning ablutions in one of the pools.